Queer Places:

Assistens Cemetery, Heden 5, 5000 Odense, Denmark

Niels

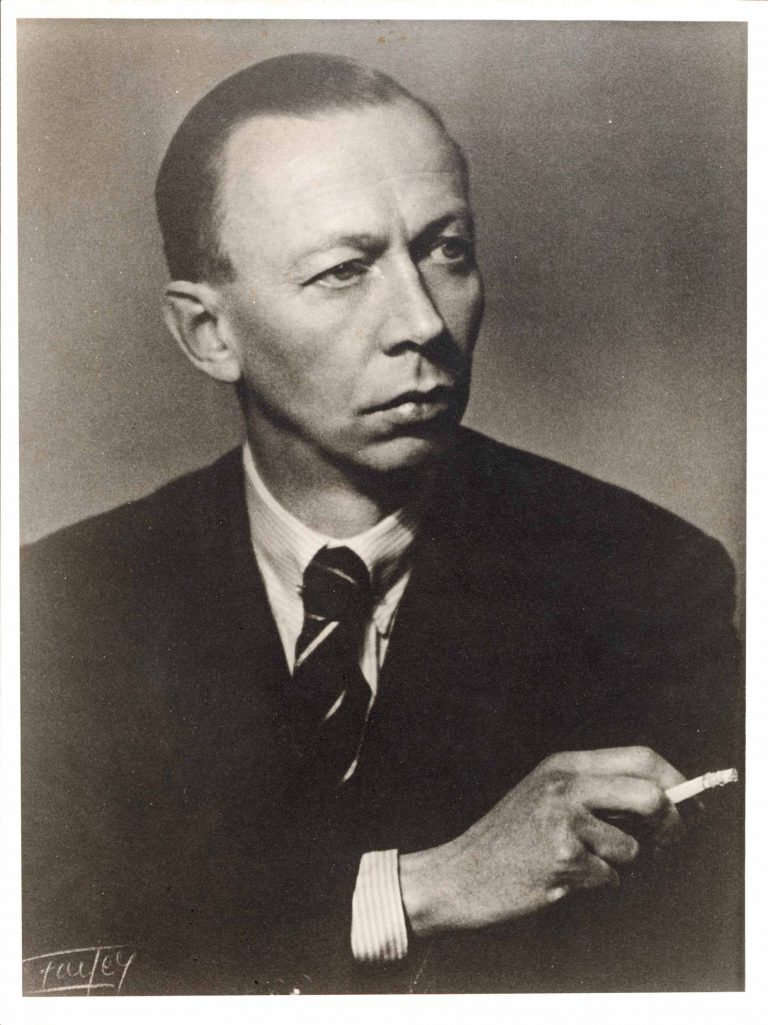

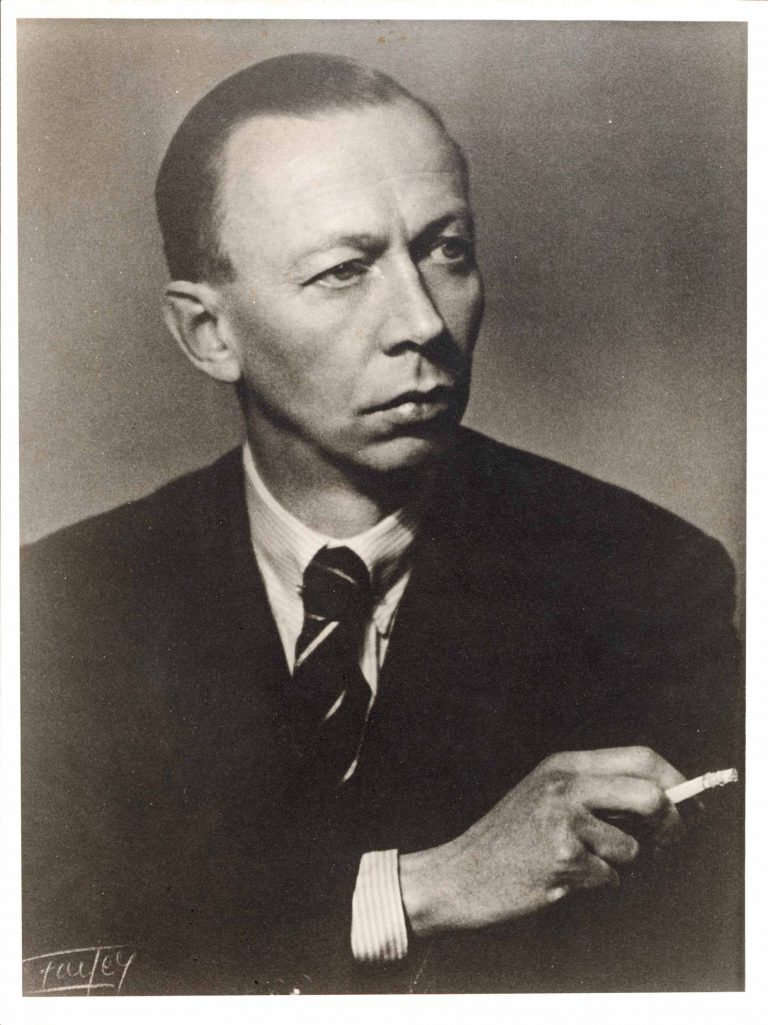

Carl Gustav Magnus Rasmussen (August 10, 1895 - September 13, 1953) was a

Danish diplomat and foreign minister. After graduating in law, Rasmussen in

1921 entered the Danish foreign service. His career was brilliant. As an

advocate for Denmark at the International Tribunal in The Hague, Rasmussen

played a decisive role in the Danish– Norwegian dispute over Greenland (1932–

1933). During World War II he was deputy to the Danish minister in London.

When the Danish Legation in London in 1941 declared itself independent of the

government of Denmark (under German occupation), Rasmussen was dismissed from

the foreign service. After the war he was reinstated and although he had no

experience or background in party politics, he was appointed foreign minister

in the traditionalist-agrarian (Venstre Party) government (1945– 1947). The

prime minister, Knud Kristensen, who was a farmer, is said to have been

surprised and disgusted when told that Rasmussen was a practising homosexual

and that he lived with his chauffeur. Rasmussen continued as minister of

foreign affairs in the Social Democratic government (1947– 1950), but had no

decisive influence on Denmark's entry into the Atlantic Pact in 1949. In

parliament Rasmussen attacked Kristensen, the former prime minister, for his

inadequate understanding of foreign policy. It was, on the other hand,

Rasmussen's weakness that, as a career diplomat, he had little understanding

of party politics.

Niels

Carl Gustav Magnus Rasmussen (August 10, 1895 - September 13, 1953) was a

Danish diplomat and foreign minister. After graduating in law, Rasmussen in

1921 entered the Danish foreign service. His career was brilliant. As an

advocate for Denmark at the International Tribunal in The Hague, Rasmussen

played a decisive role in the Danish– Norwegian dispute over Greenland (1932–

1933). During World War II he was deputy to the Danish minister in London.

When the Danish Legation in London in 1941 declared itself independent of the

government of Denmark (under German occupation), Rasmussen was dismissed from

the foreign service. After the war he was reinstated and although he had no

experience or background in party politics, he was appointed foreign minister

in the traditionalist-agrarian (Venstre Party) government (1945– 1947). The

prime minister, Knud Kristensen, who was a farmer, is said to have been

surprised and disgusted when told that Rasmussen was a practising homosexual

and that he lived with his chauffeur. Rasmussen continued as minister of

foreign affairs in the Social Democratic government (1947– 1950), but had no

decisive influence on Denmark's entry into the Atlantic Pact in 1949. In

parliament Rasmussen attacked Kristensen, the former prime minister, for his

inadequate understanding of foreign policy. It was, on the other hand,

Rasmussen's weakness that, as a career diplomat, he had little understanding

of party politics.

When the Permanent Under-Secretary of State had to resign in 1948 after

having ‘taken over’ the wife of a newly wedded colleague in the foreign

service, Rasmussen appointed his close friend,

Jens Rudolph Dahl (1894– 1977),

Permanent Under-Secretary. Dahl was a homosexual and two years later he too

had to resign after having made homosocial advances to a young diplomat.

After the fall of the Social Democratic government in October 1950,

Rasmussen was appointed ambassador in Rome. Dahl also settled in Rome and took

up a career as a newspaper commentator. Although it was widely known that

Gustav (aka ‘Gysse’) Rasmussen was a homosexual, the general public was not

aware of it. However, in December 1950 Rasmussen was attacked in a provincial

newspaper affiliated with the Venstre Party for having appointed Dahl. A well

known former diplomat wrote that homosexuals had a natural tendency to form

cliques and coteries closed to ‘normal’ people, declaring that the US House

Committee on Un-American Activities was decidedly correct in its view of

homosexuals as ‘particularly dangerous persons’. However, according to younger

collegues, Dahl, after his resignation, retained to an amazing degree the

respect and affection of his former collegues, whom he regularly visited at

the Foreign Ministry.

That the Foreign Ministry (but not foreign policy) during the post-war

years was led by homosexual civil servants may in the longer perspective have

contributed to the relaxed attitude towards homosexual personnel which has

since characterised the Danish foreign service.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- Robert Aldrich and Garry Wotherspoon. Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian

History Vol.1: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century: From Antiquity

to the Mid-twentieth Century Vol 1 (p.365). Taylor and Francis. Edizione

del Kindle.

Niels

Carl Gustav Magnus Rasmussen (August 10, 1895 - September 13, 1953) was a

Danish diplomat and foreign minister. After graduating in law, Rasmussen in

1921 entered the Danish foreign service. His career was brilliant. As an

advocate for Denmark at the International Tribunal in The Hague, Rasmussen

played a decisive role in the Danish– Norwegian dispute over Greenland (1932–

1933). During World War II he was deputy to the Danish minister in London.

When the Danish Legation in London in 1941 declared itself independent of the

government of Denmark (under German occupation), Rasmussen was dismissed from

the foreign service. After the war he was reinstated and although he had no

experience or background in party politics, he was appointed foreign minister

in the traditionalist-agrarian (Venstre Party) government (1945– 1947). The

prime minister, Knud Kristensen, who was a farmer, is said to have been

surprised and disgusted when told that Rasmussen was a practising homosexual

and that he lived with his chauffeur. Rasmussen continued as minister of

foreign affairs in the Social Democratic government (1947– 1950), but had no

decisive influence on Denmark's entry into the Atlantic Pact in 1949. In

parliament Rasmussen attacked Kristensen, the former prime minister, for his

inadequate understanding of foreign policy. It was, on the other hand,

Rasmussen's weakness that, as a career diplomat, he had little understanding

of party politics.

Niels

Carl Gustav Magnus Rasmussen (August 10, 1895 - September 13, 1953) was a

Danish diplomat and foreign minister. After graduating in law, Rasmussen in

1921 entered the Danish foreign service. His career was brilliant. As an

advocate for Denmark at the International Tribunal in The Hague, Rasmussen

played a decisive role in the Danish– Norwegian dispute over Greenland (1932–

1933). During World War II he was deputy to the Danish minister in London.

When the Danish Legation in London in 1941 declared itself independent of the

government of Denmark (under German occupation), Rasmussen was dismissed from

the foreign service. After the war he was reinstated and although he had no

experience or background in party politics, he was appointed foreign minister

in the traditionalist-agrarian (Venstre Party) government (1945– 1947). The

prime minister, Knud Kristensen, who was a farmer, is said to have been

surprised and disgusted when told that Rasmussen was a practising homosexual

and that he lived with his chauffeur. Rasmussen continued as minister of

foreign affairs in the Social Democratic government (1947– 1950), but had no

decisive influence on Denmark's entry into the Atlantic Pact in 1949. In

parliament Rasmussen attacked Kristensen, the former prime minister, for his

inadequate understanding of foreign policy. It was, on the other hand,

Rasmussen's weakness that, as a career diplomat, he had little understanding

of party politics.